Who Defines Us?

Sanjivani Horstkamp Vinekar

the fundraising site for Sureshbhai Patel is here.http://www.gofundme.com/m757pw

Who Defines Us?

Sanjivani Horstkamp Vinekar

the fundraising site for Sureshbhai Patel is here.http://www.gofundme.com/m757pw

Who Defines Us?

Where do we fit in? Growing up, a first generation immigrant with strong ties to my cultural roots, I always had a strong sense of my own history. The oral history of my community went so far back as even to take on some fantastical mythical elements. I knew where I came from, why, and for what purpose. But, we were new to the U.S. None of the history that I considered MY history, included any experience here, yet. Back in those days of my childhood, there was no hyphenated label for us. We green-card-holders still called ourselves Indians. It never occurred to us to call ourselves Indian-Americans, not even years later after we all had finally accepted the fact that it was highly unlikely we would ever move back to India. Not even after we had traded in our green cards for U.S. passports. Our history was still the history that took place in our homeland and continued in Indian-only dinner parties and Diwali festivals in university auditoriums. We felt little connection to the mainstream culture surrounding each of our families and no sense of history in our new home. And, the term "Indian-American," was one that showed up for us only recently.

As a general rule, the history that endures is primarily the history of the power-holders in any society. The history of everyone else appears only incidentally in support of the power-holders' narrative or not at all. Those who are not among the power group do not get to define their own history for posterity. Their history is defined for them by someone else. Groups who could not be omitted from the historical narrative, like the Africans brought to the U.S. as slaves, were included in the history, albeit largely inaccurately or with harms minimized and as props for the main narrative. Other minority groups were simply omitted. It isn't surprising, then, that growing up, I was never taught about the history of Indian immigrants in the United States and their importance to the civil rights movement. While my parents had told me about the limits on immigration of Indians, which I learned later was the Asian Exclusion Act of 1924, this history or any other mention of Indians in the U.S. for that matter almost never makes it into the school history textbooks of this country's schools.

The current growing pains surrounding what is taught as U.S. History in American public schools have placed a spotlight on who, exactly, is shaping the historical narrative of minority groups. Heretofore "invisible," groups are finally asserting their own historical perspective and demanding to define their own places in that narrative. Those who have benefited from a self-serving historical narrative are understandably resistant to the inclusion of narratives that might shed light on oppression. This tug-of-war is in itself an important part of U.S. history. It illustrates a shifting demographic balance in the country. The ethos is a welcome one as I anticipate the Indian-Americans finally defining for ourselves our own community's place in the national historical narrative.

The natural evolution of who gets to write history, however, is not well-received by those who have been used to defining history by themselves. Over the last several months, the stories of various school boards' and even legislatures' attempts to impose ideological limitations on school history curricula have caught the world's attention. In Arizona, an attempt to ban "ethnic" education was imposed by legislation recently. Other states are following suit. Most recently, an Oklahoma legislator, who is a member of a group whose mission includes to "restore to its rightful place the [Christian] church in America (indeed, the entire earth)," has begun the process to make the teaching of Advanced Placement (AP) US History illegal in the public schools. The general aim of all of these efforts has been the resistance to groups who used to be comfortably "invisible," now shaping their own historical narratives.

Like most Indian-Americans who were educated here, I also took AP U.S. History in high school. It was very interesting, but East Asian Indians were entirely absent from the narrative. Even so, certain parts of the prevalent viewpoint being presented felt relatable to my own experience. One of those is the Horatio Alger myth, or the enduring myth of the poor downtrodden boy who pulls himself up by his bootstraps and becomes a successful American adult. Horatio's fictional adventures illustrated the idea of the "American Dream."

Perhaps the reason the Horatio Alger myth hit home and remained with me is because it fits the story of not only my own family but all the Indian families around me. In fact, the little Indian immigrant community in which I grew up was so small that I didn't know there existed any other Indian immigrant experience other than rising from nothing to success via hard work! Yet, when it came to the appearance of the Horatio Alger myth in our school history classes, Indian immigrants were entirely absent. Only European immigrants were included in the narrative of the role immigrants played in building this country. The Irish JFK. The Italians. The Scandinavian farmers who settled into the Midwest. The European Jews. Indians, who had been in the U.S. since the 18th century, were nowhere to be found in the telling of U.S. history in American schools. For the U.S. population at large, the Horatio Alger myth evokes in minds images of immigrants of European ethnicity, beginning with our first Secretary of the Treasury, Alexander Hamilton, ethnically French and Scottish. Yet, in my own experience, the first time I saw the nation become aware of the similar narrative for Indian immigrants, sadly, was when one of them was brutalized by law enforcement due to the color of his skin.

The story of Sureshbhai Patel and his son follows a path common to a large fraction of Americans. Sureshbhai was a poor farmer who BELIEVED in the promise of the American dream. His belief in that dream required more than cheering on American progress. His belief in the American dream required more than buying American products or cheering for American sports teams or wearing clothing with "USA," emblazoned on it. His belief required more than investing in American companies. His belief in that dream was so strong that he sent his very own son away from the only home the son knew to participate in building it. It is not easy for any loving parent and countryman to send his own child, the product of years of care and teaching, who could contribute to the future of his own country, away from home to contribute to the strength of another country. Yet, that is exactly what countless families around the world have done. The modern America we enjoy today has been built up and shaped largely by immigrants whose family invested not money but their own children into the enterprise of building a better America. These are families around the world who invested into the project of building America the minds and bodies of their very own children.

Sureshbhai encouraged his son to go far away to America for a bright future. The son left his family and roots behind and came to this country. He learned English well enough to complete an undergraduate degree in electrical engineering in the U.S. He became an American citizen. He got a job and became fully-employed. He bought a modest house in a safe neighborhood where he could raise his family. He paid income taxes and property taxes which support American institutions. He started work to get a graduate degree in engineering. The U.S. needs graduate level engineers. He supported his wife and baby and helped his parents. And, once Sureshbhai's son had worked so hard and established himself as a full-fledged American, Sureshbhai departed from his own wife and farm back home to visit his son's new home to help care for his grandson. This family's story is the AMERICAN DREAM, if I ever heard of one.

But, here is where the narrative of the Indian who loves America diverges from the European who loves America. Here is where the Indian experience becomes different. Like the vast majority of Indians, Sureshbhai has dark skin. This was enough for a neighbor to consider him NOT someone who has given his own son to help build up America. NOT a friendly neighbor. No. Sureshbhai's dark skin was the impetus for a neighbor to call 911 because that dark skin made Sureshbhai, out taking a morning walk, "suspicious." So "suspicious," in fact, that the neighbor felt afraid of going to work and leaving his wife at his house. The American dream began to unravel.

Now, Sureshbhai, who made a living as a farmer, may not be able to grip the handle of a shovel. His neck has been broken by an American police officer. The police officer never gave Sureshbhai the benefit of the doubt, not even when that officer ascertained that Sureshbhai was an older Indian man who spoke no English. The police officer never once stopped to think that perhaps Sureshbhai is an old grandfather taking a morning walk. Because Sureshbhai's skin is dark. The police officer broke Sureshbhai's neck.

Sureshbhai's son, who needs assistance caring for a child with health issues, is now anticipating the arrival of the medical bills for his father's medical treatment. The U.S. has the highest health care costs of any country on the earth. Sureshbhai required a double spinal fusion surgery because of the injuries sustained from the police officer's actions. In general, the costs in the U.S. for surgeries and hospitalization can run into the tens of thousands of dollars. If Sureshbhai's son cannot pay those bills, the American dream his father and he sacrificed so much for will result in their financial ruin. While a lawsuit is pending and may take up to a year or more to conclude, damage awards are unlikely to come through before the hospital bills come due. The family's hard-earned credit will be destroyed. Although Indian-Americans are called the "model minority," being called a "model minority" is not enough to set us apart from the same risks that all dark-skinned people in this country face. While we may be perceived differently from other dark-skinned minorities in this country in some ways, in the way our skin color is perceived, we are not different. We are "suspicious."

When the story of Sureshbhai Patel hit the news, my first reaction was shock. The dash-cam video of the old slender grandfather taking a walk and then getting brutalized by three young police officers hit too close to home. It could have happened to my own grandfather who had come here and also taken walks. It could have happened to any of my older uncles. Though, this incident is an extreme manifestation of low-level racism all dark-skinned people, including Indian-Americans, face frequently, that it happened to a helpless grandfather who could have been any of our grandfathers forces our Indian-American community to face the fact that we are not white. We Indian-Americans are not white, no matter how much we align ourselves with the white culture and distance ourselves from other dark-skinned minorities. Even if fans paint portraits that show our Indian-American governors as having white skin, in reality, the skin is brown. Nothing we can do will make us white in the eyes of some Americans. Our American experience is different from the Horatio Alger myth because, in the eyes of most European-Americans, our skin color makes us indistinguishable from African-Americans or Latino-Americans, two minority groups that Indian-Americans, we must admit, go to lengths to establish a hard line of separation from. Yet, our experience is not that of the African-American community. Our experience is not that of the Latino-American community. When our experience as the dark-skinned model minority through the unfortunate experience of Sureshbhai Patel came to the attention of the entire world, it gave us the opportunity to shape our own narrative. It is a turning point. We, as a community, have the power now to express who is going to write that narrative. Will it be us? Or will we remain the largely "invisible," model minority when it comes to the story of where we fit into the narrative of American civil rights and racial interactions?

I wish it would be we who write our own history of an American community. I wish we would step up to the challenge of shaping our own history in this country. We, the most highly educated and wealthiest American minority group, are entirely capable of doing so. As a community, we were the ones who finally stood up to the British and made them leave the country of our roots. We as a community have it within us to shape our own narratives. I know this. The history I grew up hearing about my own small community has never been shaped by outsiders. It is an oral history passed down through the generations, generations of grandmothers and grandfathers, until my parents told me and I tell my own children. I waited for the public outcry, the numerous Indian-American voices who would insist that this should never have happened and should not happen again. I waited to see a broad show of solidarity with the Patel family. More and more media outlets covered the story. The Indian government had stepped in. Where were the voices of Indian-Americans on the ground?

The Western media was already shaping the narrative of our experience. One headline in a major American news outlet is "Ala. Governor Apologizes to India After Rough Arrest." Rough arrest?!? This terminology insinuates that Sureshbhai did something wrong to get arrested, when the truth is that he was taking a morning walk. The American media has deliberately chosen words to insinuate blame on Sureshbhai Patel, the victim. When outsiders shape the narrative, the image they project minimizes wrongdoing and invents blame where there should be none. Another American headline reads, "Indian Man Injured by Alabama Police; Government 'disturbed.'" Injured?!? This grandfather was not merely injured. His neck was broken resulting in likely paralysis and life-long loss of motor function. Again, the American media have chosen words that minimize what happened. Had Sureshbhai been a white man whose neck was broken and was left paralyzed by a black man, would the headline have used the term "injured?" The narrative of how the Indian-American community fits into the history of American civil rights is being shaped before our eyes. Where is our voice?

I waited for the outcry among my Indian-American friends on social media.

A large number of my Indian-American Facebook friends had posted videos of themselves and their children dumping ice on their heads to participate in the ALS ice bucket challenge. 93% of victims of ALS are of European ethnicity, in other words, white-skinned. Kudos to our Indian-American community for participating so energetically in the effort to help the victims of that devastating disease! It is a terrible disease and we should all contribute to supporting efforts to combat it.

I waited for the same energy when it came to shaping the narrative of our own community.

I am still waiting.

So far, the number of my Indian-heritage (that includes Indian-American and Indians in other countries) Facebook friends who have posted a single item about what happened to Sureshbhai Patel can be counted on one hand. Of the posts that have been made, the comment response by Indian-Americans has been surprisingly minimal.

Why are we so ready to support the majority group's interests but so tentative when it comes to showing our vocal support for our own group's rights? Are we afraid to rock the boat? Are we afraid to offend someone if we publicize our dismay? Are we afraid of repercussions in our social or professional circles? I have no idea. But, surely, the implications of the paralysis of an uncle at the hands of a law enforcement officer because of Uncle's skin color ought to be as important to us if not more so than the ice bucket challenge? What does this say about our community? Is keeping mum, passivity and acquiescence the required character traits for us to be honored with the label of "model minority?"

To be fair, our Indian-American community has come a long way since the 1790 arrival of the Madrasi man in Massachusetts. But, how many of us know that the U.S. Supreme Court, by UNANIMOUS decision, stripped all Indian-Americans of their U.S. citizenship in 1923 (United States v. Bhagat Singh Thind) for the sole reason that Indian-Americans' skin is not white enough? According to abagond.wordpress.com, Bhagat Singh Thind " ... arrived in the US in 1913 to study at the University of California, Berkeley, getting a PhD. In 1918, he served in the US Army during the First World War, rising to the rank of Acting Sergeant. He was honourably discharged. The Army said his character was “excellent”." (Quoted from abagond.wordpress.com) This is a narrative that is invisible from the story of American civil rights that is taught in the classroom. How many of us know it? How many of us have told this story to our children? Even as we boast an Indian-American surgeon general, two Indian-American state governors, an Indian-American state attorney general, where are our voices when it comes to shaping our own historical narrative as Americans?

Indians have been participating in the building and shaping of America since 1790. When will we feel bold enough to write our own historical narrative, to define for ourselves how we will be remembered in history rather than letting others define us? Nature abhors a vacuum and so does historical narrative. If we, as a community, do not raise our voices and let the world know what is acceptable to us and what is not, then we risk the same kind of externally imposed narrative other groups have faced. Did the slaves of the Confederate South really willingly take up arms to defend their masters and the curious institution? It is impossible for any reasonable person to believe, and yet, this narrative is being asserted. Are we not bothered when an uncle is paralyzed for taking his morning walk? If we do not speak up now, that may be how our community, the model minority, is remembered. Sureshbhai's story will go down in history as a suspicious Indian man who was arrested and injured. Who defines us?

UPDATE #3

9 DAYS AGO

Update on Sureshbhai:

“Mr. Patel was transferred to a local rehabilitation center on Monday. He has a long, difficult, and uncertain rehabilitation process ahead of him. Mr. Patel and his family deeply appreciate the outpouring of prayers and support he has received.” – Hank Sherrod

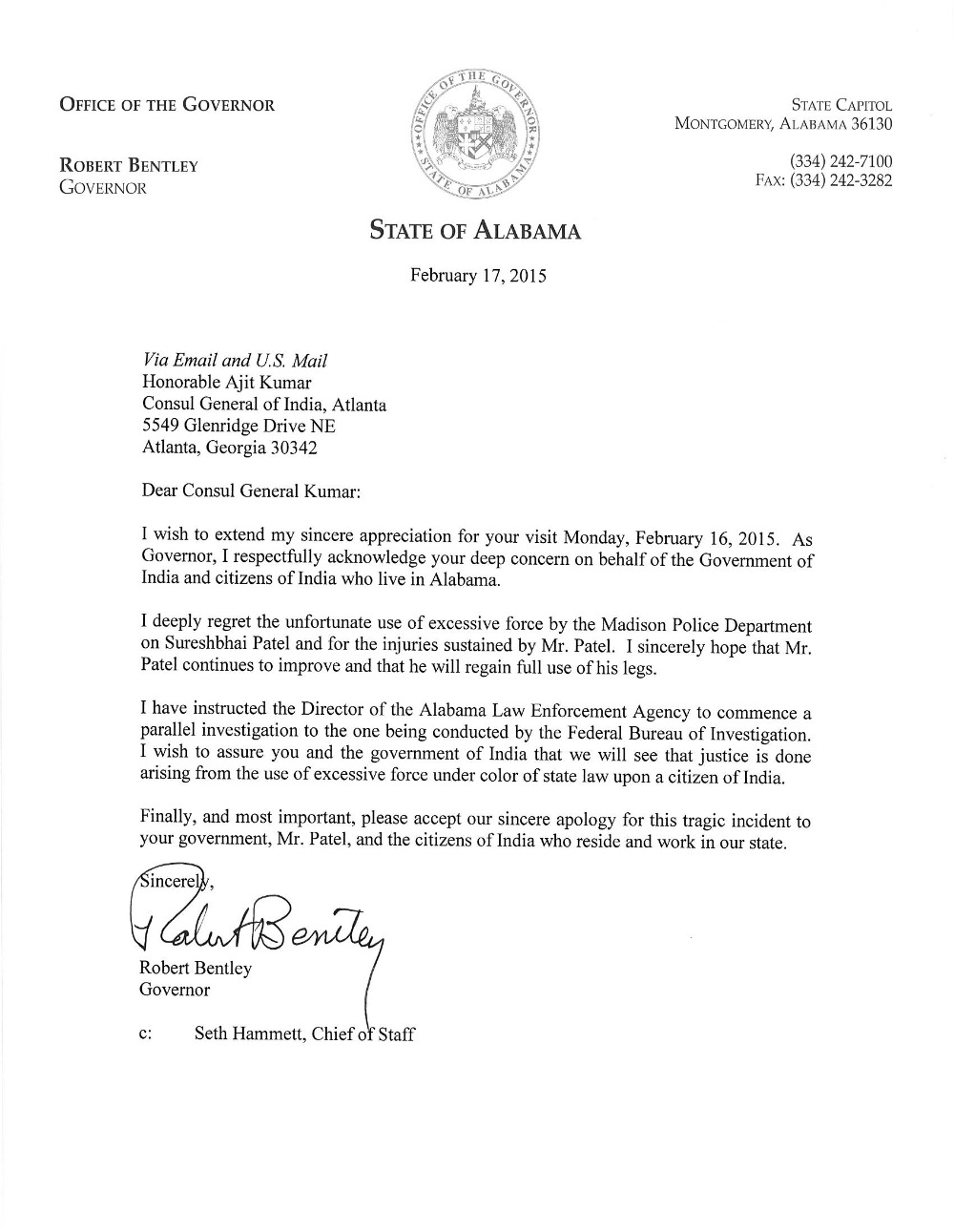

Robert Bentley, Governor of Alabama, issues an apology:

"I deeply regret the unfortunate use of excessive force by the Madison Police Department on Sureshbhai Patel and for the injuries sustained by Mr. Patel. I sincerely hope that Mr. Patel continues to improve and that he will regain full use of his legs."

Get Well Cards:

With the approval of the family and lawyer, a Get Well Card campaign has been organized by a supporter in Seattle. Feel free to send Sureshbhai a note wishing him well and showing your support for his recovery at the following address: Mr. Sureshbhai Patel, Health South Rehabilitation Hospital, 107 Governors Drive, Huntsville, AL 35801.

Thank you for your support and please continue to share Sureshbhai's story.

“Mr. Patel was transferred to a local rehabilitation center on Monday. He has a long, difficult, and uncertain rehabilitation process ahead of him. Mr. Patel and his family deeply appreciate the outpouring of prayers and support he has received.” – Hank Sherrod

Robert Bentley, Governor of Alabama, issues an apology:

"I deeply regret the unfortunate use of excessive force by the Madison Police Department on Sureshbhai Patel and for the injuries sustained by Mr. Patel. I sincerely hope that Mr. Patel continues to improve and that he will regain full use of his legs."

Get Well Cards:

With the approval of the family and lawyer, a Get Well Card campaign has been organized by a supporter in Seattle. Feel free to send Sureshbhai a note wishing him well and showing your support for his recovery at the following address: Mr. Sureshbhai Patel, Health South Rehabilitation Hospital, 107 Governors Drive, Huntsville, AL 35801.

Thank you for your support and please continue to share Sureshbhai's story.

Governer Bentley - Apology Letter

No comments:

Post a Comment